A year ago, in a bid to up my personal style game, I got a doublefinger ring, also known as knuckle ring, from an indie brand. As the name suggests, you wear it on two fingers, but the abstract design flanked four. For the most part of the day, my left hand was rendered unusable. It was the most uncomfortable piece of accessory I had worn. And yet the most complimented.

So, when trend forecasters in 2025 foretell the reprise of big, sculptural and unusual jewellery—my oversized ring is a part of the starter pack, at best—I get it.

Sculptural jewellery—pieces that blur the line between adornment and art—has been around since the 1930s when Alexander Calder created handforged brass and silver works. But it was Tiffany & Co’s Bone Cuff by Elsa Peretti that cemented the trend. The iconic piece completed 50 years last year. To coincide with that, Tiffany & Co introduced new shapes, heralding a return of unusual jewellery which, for the last three-four years, was riding high, thanks to the Italian luxury brand Schiaparelli’s outthere designs.

HAVE IT RARE

Nitya Arora, founder of luxury fashion jewellery brand Valliyan, is happy to announce that the trend has reached India. For an early mover in the segment—she started 18 years ago—Arora is finally seeing the movement she always wanted: “Pieces I used to make for the ramp or fashion editorials— wild designs like headgears and harnesses—were lying in my stockroom. Of late, so many people have come asking for these unique pieces that they are pretty much sold out.” Arora thanks the new jewellery consumer who seeks one-of-a-kind pieces.

The Bone Cuff broke through the clutter decades ago because it was curiously shaped, unassuming yet captivating—an aesthetic it shares with current sculptural jewellery. Take Goa-based Manifest Design, started by sculptor and jewellery designer Manreet Deol with her late brother Samraat in 2013. Each piece starts as a clay sculpture. Their maiden collection, Totems, targeted Indian women who were just starting to look past precious material jewellery but nothing ethnic, traditional, or junk. Deol says, “The goal was to establish a new vocabulary for contemporary Indian design that was not borrowing elements from our artisanal heritage or what the West calls contemporary.”

Manifest retails at Rs 500-6,000 and uses mainly brass and aluminium. Deol feels that this segment in jewellery is growing because of women. “As urban Indian women get more self-reliant, more confident, earn more and generally have more autonomy over their desires, they are finally exercising their choices. Women are seeking unique pieces that are like talismans of their more confident, independent lives,” she says. It’s a women-supportwomen moment where, she says, women want to back female entrepreneurs.

SLEIGHT OF HAND

People are ready to take creative risks, says designer Amit Hansraj who wears manyhats, jewellery designer being one of them. After spending over 20 years in fashion, he launched his Delhi-based clothes brand, inca, in 2020. In 2023, his watch jewellery— arm cuffs and necklaces made with classic watch dials—broke the internet. He believes that his jewellery, if one is not wearing it, can be put on the mantelpiece. Working mainly with “found objects” that he chances upon in Old Delhi shops and flea markets, he creates jewellery on what he feels “at the moment” and calls his studio “his lab”. He says, “The watch pieces clicked because people are looking for some eccentricity, missing from the cookie-cutter world of fashion. They resonated with my jewellery—made by hand, in a small-batch production.”

Made by hand is a flex in luxury. Arora recalls that when she started out, she would have to explain to the consumer why her pieces don’t have the machinemade finish. But in 2025 people seek the imperfection of handmade. She says, “Someone told me that a mug from Pottery Barn looks really good, but it does not have the uniqueness a handmade porcelain mug in a workshop in Japan has. People are craving something that takes time to make, something that is made by hand, something that is not perfect.”

Bengaluru-based jewellery artist Aman Poddar, who founded Studio Naam, will have you know that artisanal sculptural jewellery checks all those boxes. Poddar, who works mostly with gold, tinkers around in his workshop for hours to create his pieces, mainly earrings. He crafts microscopic elements from gold wire or sheet and solders each one by hand. Some of his pieces take up to 200 hours. A one-man army, Poddar doesn’t repeat pieces. He says, “Studio Naam is more of an artistic pursuit than a business one. I identify as an artist, not a jeweller. I don’t have any collections or lines.” But he has found his audience. At his last exhibition at the Oberoi Art Fair in Delhi in February, he sold nearly 70% of his works. His earrings range from Rs 2.5 lakh to Rs 5.5 lakh.

People want uniqueness, he says, “With people who come to me, there’s no conversation about choosing traditional or not, because they have already made that decision. I guess people are a bit tired of the usual.”

SHOW YOUR METAL

Being away from the usual was the turning point for jewellery designer Suhani Parekh, who was trained as a sculptor. Her Misho has pioneered metal couture in India. In 2023, a very pregnant Parekh created a 24 ct gold-coated belly armour for her bump for the opening gala of the Nita Mukesh Ambani Cultural Centre in Mumbai. It was her first piece of metal couture. “It is trickling down now. Looks on the red carpets, runways or editorials take years to normalise. But we are already getting requests from brides for metal corsets,” she says.

Misho’s corsets have a global clientele. “While designers usually turn into jewellery designers, we are the first ones to get into clothes via jewellery,” she says. Parekh creates the look around her hero piece—the customised armour, bustier or corset. She’s launching a ready-to-wear variant of her metal corsets in cheaper metal that starts at Rs 3 lakh while the bridal couture starts at Rs 5 lakh.

While her everyday-wear jewellery stays on course, Parekh sees a new opportunity in architectural forms of adornments. She says, “How we approach jewellery has been changing for years. I believe there’s nothing as transformative as jewellery in your wardrobe. People pick a piece that shows what their values are and says something about their personality.”

Alka Pande, curator and art consultant, says India’s material culture, which dates to the Indus Valley Civilisation, has been changing with each passing century: “A jeweller was an artist even then, but there were certain kinds of canons for jewellery. It was part of the cultural construct of the streedhan. Within India’s modernity, we later became influenced by western concepts, whether it was De Beers or Cartier.” The story of how we consume jewellery is one of India opening up, Pande notes. “As people started travelling, tastes changed, styles changed,” she says, adding, “Jewellery has become more about the taste of the individual, their identity and style statement that women, in particular, make. So instead of jewellery being a tool of personal wealth, it has also become a signifier of identity, taste and style.”

Valliyan’s Arora says the travelling Indian fuels her brand. “Our polki collection is designed for the audience who is attending a destination wedding in Italy and planning a summer holiday in France. They want to carry one pouch of jewellery that works for all scenarios.”

GOING BEYOND GOLD

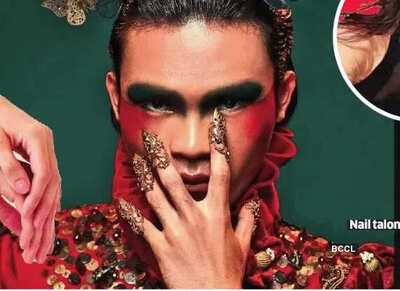

Designer Kavya Potluri says she is finally seeing people taking risks with their wedding style beyond gold, especially in traditional markets like her city Hyderabad. She is known for her artistic and intricate work in classic Indian styles but gives it a new identity with nail talons, hand harnesses and metal buns. She says custom orders have gone up from 20 a month to 80. Potluri says the new-age wedding shopper doesn’t want just gold, although creating a niche as a non-gold artistic jeweller has not been easy for her. What helped was some celebrity appearance. She says, “Most people struggle with having their own opinions. Even if they like something, they won’t wear it unless they see someone famous in it.” What has also helped, she says, are the high prices of gold.

Gold can never go out of fashion in a market like India but Studio Metallurgy founder Advaeita Mathur says now there’s space for brands like hers to co-exist. Founded in 2015, Studio Metallurgy works with brass and silver. While she loves creating chokers, ear cuffs and palm cuffs, she also has haathphools “as a reality of catering to a market that is quintessentially bridal and occasion-driven”.

“Sculptural jewellery is more visible now because more and more Indians are travelling abroad and there’s higher disposable income,” she says. “Also, a lot of us already have our staple of gold jewellery.”

Mumbai-based Bhavya Ramesh says jewellery is still an investment, a reason why she chooses to work with silver. This engineerturned-contemporary jewellery designer’s silver sunglasses and nail rings have found a cult status. She says social media has played a big role. “It allowed me to put my work out there directly and build a community that understood my vision. My concept of jewellery has always been about self-expression rather than adornment—pieces that are tactile, emotional and slightly unusual,” she says.

For Mathur, the entry point into sculptural jewellery was the simple fact that she never found it in India.

ALMOST ART

Sisters Sasha and Kaabia Grewal, who founded Outhouse in Mumbai in 2012, attribute the rise of sculptural jewellery to three engines. Sasha lists them: “A cultural appetite for objects that read as art, platforms (like social feeds and red carpets) that reward visual drama, and investment in meaning rather than metal weight.” She adds, “Luxury maisons and independent ateliers are turning to three-dimensional forms and technical bravura because they give buyers something rarer than carats: a story and a point of view.”

Storytelling, says Mathur, is at the heart of conceptual jewellery. Manifest’s consumers, confirms Deol, want to be part of an artistic movement rather than a commercial exchange.

Sarath Selvanathan, founder of Mookuthi—a Chennai-based brand that only makes nose ornaments in gold and precious materials—says no object is too small to carry the weight of craft, tradition and design. “In 2015, when I made the first nose ornament for a friend, I realised it was the smallest ornament I’d made but the only one that changed the way the wearer looked.” They cater to a community that looks at jewellery as identity, expression, or memory. “What we’ve learned is that jewellery isn’t just about taste, it mirrors where someone is in their life and how ready they are to embrace it.”

Kaabia o f Outhouse says there is a grow- ing appetite in India for design that feels daring and deeply personal. “Our sculptural ear cuffs, body harnesses and statement bralettes are not bound by occasion—they are worn as extensions of individuality, on the red carpet, at destination weddings, or styled as everyday art.” The Grewals believe that luxury no longer equals scarcity of material, it increasingly equals how scarce an idea is. Sasha elaborates, “Storytelling, provenance, technique and the illusion of singularity (limited editions, bespoke) are the currency. Craftsmanship is marketed as the plot of the product—how it was made, who made it, the narrative it carries. That is precisely why maisons are investing in narrative-rich high jewellery: they are selling meaning as modern heirlooms.”

Meaningful jewellery and contemporary narratives drive Frostbite Lab. The Mumbai based everyday streetwear jewellery brand was started by Shrikesh Choksi and owes its claim to fame to the teeth grilles that went viral. Choksi customises the grille to each mouth and it can cost up to Rs 2 lakh, depending on the scale of ornamentation. He has been getting requests for grilles in Tamil script and Gurmukhi and has even experimented with meenakari. “People want unusual jewellery as it’s a source of wearing their identity, especially younger customers, who are more experimental, tapped into social media and exposed to trends.”

Sasha of Outhouse says they created interesting pieces like bralettes, ear suites and hand harnesses after listening to clients and stylists. “We introduced these categories because we saw them perform— in shoots, on influencers, at trunk shows—and because they solved a simple brief: give someone a single piece that transforms an outfit.” Ramesh says there’s still hesitation in the precious jewellery segment to break the mould, because experimentation feels risky in a space that has been traditional for centuries. Brands like hers fill that gap.

DESIGN OF THE TIMES

Pande notes that the way Gen Z wears jewellery is very different but what has also helped in growing the niche is jewellery design as a subject. “Young designers wentabroad to specialise in jewellery design and came back with great ideas, and the materiality of jewellery changed,” she says.

“People, women in particular, are more and more confident of themselves, and they are wearing jewellery not to carry their wealth with them but to make a statement of their self-assurance.”

According to Mathur, the next area of attention for brands should be the underserved niche of unusual items like grilles and men’s jewellery. Ramesh says her consumer is someone who wants to try something new: “There comes a point—no matter what age—when you feel bored or stuck. You want to step out of your comfort zone. That’s usually when people think of my brand.” For Mathur, the market potential is huge: “Most sculptural jewellery is risky in the sense that it doesn’t follow convention. It’s not subtle. It can be provocative. I’ve never met a customer who is not confident in what their style is when picking a sculptural piece. It just almost never happens.”

It’s a dopamine hit; like my knuckle ring, it may be uncomfortable but you are hooked to the attention.

So, when trend forecasters in 2025 foretell the reprise of big, sculptural and unusual jewellery—my oversized ring is a part of the starter pack, at best—I get it.

Sculptural jewellery—pieces that blur the line between adornment and art—has been around since the 1930s when Alexander Calder created handforged brass and silver works. But it was Tiffany & Co’s Bone Cuff by Elsa Peretti that cemented the trend. The iconic piece completed 50 years last year. To coincide with that, Tiffany & Co introduced new shapes, heralding a return of unusual jewellery which, for the last three-four years, was riding high, thanks to the Italian luxury brand Schiaparelli’s outthere designs.

HAVE IT RARE

Nitya Arora, founder of luxury fashion jewellery brand Valliyan, is happy to announce that the trend has reached India. For an early mover in the segment—she started 18 years ago—Arora is finally seeing the movement she always wanted: “Pieces I used to make for the ramp or fashion editorials— wild designs like headgears and harnesses—were lying in my stockroom. Of late, so many people have come asking for these unique pieces that they are pretty much sold out.” Arora thanks the new jewellery consumer who seeks one-of-a-kind pieces.

The Bone Cuff broke through the clutter decades ago because it was curiously shaped, unassuming yet captivating—an aesthetic it shares with current sculptural jewellery. Take Goa-based Manifest Design, started by sculptor and jewellery designer Manreet Deol with her late brother Samraat in 2013. Each piece starts as a clay sculpture. Their maiden collection, Totems, targeted Indian women who were just starting to look past precious material jewellery but nothing ethnic, traditional, or junk. Deol says, “The goal was to establish a new vocabulary for contemporary Indian design that was not borrowing elements from our artisanal heritage or what the West calls contemporary.”

Manifest retails at Rs 500-6,000 and uses mainly brass and aluminium. Deol feels that this segment in jewellery is growing because of women. “As urban Indian women get more self-reliant, more confident, earn more and generally have more autonomy over their desires, they are finally exercising their choices. Women are seeking unique pieces that are like talismans of their more confident, independent lives,” she says. It’s a women-supportwomen moment where, she says, women want to back female entrepreneurs.

SLEIGHT OF HAND

People are ready to take creative risks, says designer Amit Hansraj who wears manyhats, jewellery designer being one of them. After spending over 20 years in fashion, he launched his Delhi-based clothes brand, inca, in 2020. In 2023, his watch jewellery— arm cuffs and necklaces made with classic watch dials—broke the internet. He believes that his jewellery, if one is not wearing it, can be put on the mantelpiece. Working mainly with “found objects” that he chances upon in Old Delhi shops and flea markets, he creates jewellery on what he feels “at the moment” and calls his studio “his lab”. He says, “The watch pieces clicked because people are looking for some eccentricity, missing from the cookie-cutter world of fashion. They resonated with my jewellery—made by hand, in a small-batch production.”

Made by hand is a flex in luxury. Arora recalls that when she started out, she would have to explain to the consumer why her pieces don’t have the machinemade finish. But in 2025 people seek the imperfection of handmade. She says, “Someone told me that a mug from Pottery Barn looks really good, but it does not have the uniqueness a handmade porcelain mug in a workshop in Japan has. People are craving something that takes time to make, something that is made by hand, something that is not perfect.”

Bengaluru-based jewellery artist Aman Poddar, who founded Studio Naam, will have you know that artisanal sculptural jewellery checks all those boxes. Poddar, who works mostly with gold, tinkers around in his workshop for hours to create his pieces, mainly earrings. He crafts microscopic elements from gold wire or sheet and solders each one by hand. Some of his pieces take up to 200 hours. A one-man army, Poddar doesn’t repeat pieces. He says, “Studio Naam is more of an artistic pursuit than a business one. I identify as an artist, not a jeweller. I don’t have any collections or lines.” But he has found his audience. At his last exhibition at the Oberoi Art Fair in Delhi in February, he sold nearly 70% of his works. His earrings range from Rs 2.5 lakh to Rs 5.5 lakh.

People want uniqueness, he says, “With people who come to me, there’s no conversation about choosing traditional or not, because they have already made that decision. I guess people are a bit tired of the usual.”

SHOW YOUR METAL

Being away from the usual was the turning point for jewellery designer Suhani Parekh, who was trained as a sculptor. Her Misho has pioneered metal couture in India. In 2023, a very pregnant Parekh created a 24 ct gold-coated belly armour for her bump for the opening gala of the Nita Mukesh Ambani Cultural Centre in Mumbai. It was her first piece of metal couture. “It is trickling down now. Looks on the red carpets, runways or editorials take years to normalise. But we are already getting requests from brides for metal corsets,” she says.

Misho’s corsets have a global clientele. “While designers usually turn into jewellery designers, we are the first ones to get into clothes via jewellery,” she says. Parekh creates the look around her hero piece—the customised armour, bustier or corset. She’s launching a ready-to-wear variant of her metal corsets in cheaper metal that starts at Rs 3 lakh while the bridal couture starts at Rs 5 lakh.

While her everyday-wear jewellery stays on course, Parekh sees a new opportunity in architectural forms of adornments. She says, “How we approach jewellery has been changing for years. I believe there’s nothing as transformative as jewellery in your wardrobe. People pick a piece that shows what their values are and says something about their personality.”

Alka Pande, curator and art consultant, says India’s material culture, which dates to the Indus Valley Civilisation, has been changing with each passing century: “A jeweller was an artist even then, but there were certain kinds of canons for jewellery. It was part of the cultural construct of the streedhan. Within India’s modernity, we later became influenced by western concepts, whether it was De Beers or Cartier.” The story of how we consume jewellery is one of India opening up, Pande notes. “As people started travelling, tastes changed, styles changed,” she says, adding, “Jewellery has become more about the taste of the individual, their identity and style statement that women, in particular, make. So instead of jewellery being a tool of personal wealth, it has also become a signifier of identity, taste and style.”

Valliyan’s Arora says the travelling Indian fuels her brand. “Our polki collection is designed for the audience who is attending a destination wedding in Italy and planning a summer holiday in France. They want to carry one pouch of jewellery that works for all scenarios.”

GOING BEYOND GOLD

Designer Kavya Potluri says she is finally seeing people taking risks with their wedding style beyond gold, especially in traditional markets like her city Hyderabad. She is known for her artistic and intricate work in classic Indian styles but gives it a new identity with nail talons, hand harnesses and metal buns. She says custom orders have gone up from 20 a month to 80. Potluri says the new-age wedding shopper doesn’t want just gold, although creating a niche as a non-gold artistic jeweller has not been easy for her. What helped was some celebrity appearance. She says, “Most people struggle with having their own opinions. Even if they like something, they won’t wear it unless they see someone famous in it.” What has also helped, she says, are the high prices of gold.

Gold can never go out of fashion in a market like India but Studio Metallurgy founder Advaeita Mathur says now there’s space for brands like hers to co-exist. Founded in 2015, Studio Metallurgy works with brass and silver. While she loves creating chokers, ear cuffs and palm cuffs, she also has haathphools “as a reality of catering to a market that is quintessentially bridal and occasion-driven”.

“Sculptural jewellery is more visible now because more and more Indians are travelling abroad and there’s higher disposable income,” she says. “Also, a lot of us already have our staple of gold jewellery.”

Mumbai-based Bhavya Ramesh says jewellery is still an investment, a reason why she chooses to work with silver. This engineerturned-contemporary jewellery designer’s silver sunglasses and nail rings have found a cult status. She says social media has played a big role. “It allowed me to put my work out there directly and build a community that understood my vision. My concept of jewellery has always been about self-expression rather than adornment—pieces that are tactile, emotional and slightly unusual,” she says.

For Mathur, the entry point into sculptural jewellery was the simple fact that she never found it in India.

ALMOST ART

Sisters Sasha and Kaabia Grewal, who founded Outhouse in Mumbai in 2012, attribute the rise of sculptural jewellery to three engines. Sasha lists them: “A cultural appetite for objects that read as art, platforms (like social feeds and red carpets) that reward visual drama, and investment in meaning rather than metal weight.” She adds, “Luxury maisons and independent ateliers are turning to three-dimensional forms and technical bravura because they give buyers something rarer than carats: a story and a point of view.”

Storytelling, says Mathur, is at the heart of conceptual jewellery. Manifest’s consumers, confirms Deol, want to be part of an artistic movement rather than a commercial exchange.

Sarath Selvanathan, founder of Mookuthi—a Chennai-based brand that only makes nose ornaments in gold and precious materials—says no object is too small to carry the weight of craft, tradition and design. “In 2015, when I made the first nose ornament for a friend, I realised it was the smallest ornament I’d made but the only one that changed the way the wearer looked.” They cater to a community that looks at jewellery as identity, expression, or memory. “What we’ve learned is that jewellery isn’t just about taste, it mirrors where someone is in their life and how ready they are to embrace it.”

Kaabia o f Outhouse says there is a grow- ing appetite in India for design that feels daring and deeply personal. “Our sculptural ear cuffs, body harnesses and statement bralettes are not bound by occasion—they are worn as extensions of individuality, on the red carpet, at destination weddings, or styled as everyday art.” The Grewals believe that luxury no longer equals scarcity of material, it increasingly equals how scarce an idea is. Sasha elaborates, “Storytelling, provenance, technique and the illusion of singularity (limited editions, bespoke) are the currency. Craftsmanship is marketed as the plot of the product—how it was made, who made it, the narrative it carries. That is precisely why maisons are investing in narrative-rich high jewellery: they are selling meaning as modern heirlooms.”

Meaningful jewellery and contemporary narratives drive Frostbite Lab. The Mumbai based everyday streetwear jewellery brand was started by Shrikesh Choksi and owes its claim to fame to the teeth grilles that went viral. Choksi customises the grille to each mouth and it can cost up to Rs 2 lakh, depending on the scale of ornamentation. He has been getting requests for grilles in Tamil script and Gurmukhi and has even experimented with meenakari. “People want unusual jewellery as it’s a source of wearing their identity, especially younger customers, who are more experimental, tapped into social media and exposed to trends.”

Sasha of Outhouse says they created interesting pieces like bralettes, ear suites and hand harnesses after listening to clients and stylists. “We introduced these categories because we saw them perform— in shoots, on influencers, at trunk shows—and because they solved a simple brief: give someone a single piece that transforms an outfit.” Ramesh says there’s still hesitation in the precious jewellery segment to break the mould, because experimentation feels risky in a space that has been traditional for centuries. Brands like hers fill that gap.

DESIGN OF THE TIMES

Pande notes that the way Gen Z wears jewellery is very different but what has also helped in growing the niche is jewellery design as a subject. “Young designers wentabroad to specialise in jewellery design and came back with great ideas, and the materiality of jewellery changed,” she says.

“People, women in particular, are more and more confident of themselves, and they are wearing jewellery not to carry their wealth with them but to make a statement of their self-assurance.”

According to Mathur, the next area of attention for brands should be the underserved niche of unusual items like grilles and men’s jewellery. Ramesh says her consumer is someone who wants to try something new: “There comes a point—no matter what age—when you feel bored or stuck. You want to step out of your comfort zone. That’s usually when people think of my brand.” For Mathur, the market potential is huge: “Most sculptural jewellery is risky in the sense that it doesn’t follow convention. It’s not subtle. It can be provocative. I’ve never met a customer who is not confident in what their style is when picking a sculptural piece. It just almost never happens.”

It’s a dopamine hit; like my knuckle ring, it may be uncomfortable but you are hooked to the attention.

You may also like

'After growing big...': Karnataka deputy CM Shivakumar on Majumdar-Shaw criticising Bengaluru infra; accuses her of 'forgetting roots'

Besides royal titles, is Prince Andrew set to lose his place at Prince William's coronation? Here's what the report says

"No one pays single penny without knowing market value": Sudhir Chaudhary on being called highest-paid govt employee

Himachal Pradesh Governor, CM Sukhu, Dy CM Agnihotri extend Diwali greetings to people

Feeling bloated like a balloon despite eating right? Nutritionist reveals surprising causes and easy tricks to cure a gassy gut